I hope it’s OK if I repost a question I asked on B-Greek last week, and to which I haven’t received any replies.

συγγνώμονάς τοι τοὺς θεοὺς εἶναι δόκει,

ὅταν τις ὅρκῳ θάνατον ἐκφυγεῖν θέλῃ

ἢ δεσμὸν ἢ βίαια πολεμίων κακά,

ἢ παισὶν αὐθένταισι κοινωνῇ δόμων.

[Euripides, Fragment 645 in Nauck]

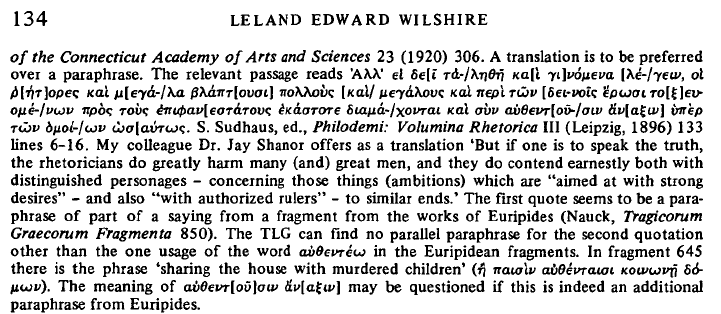

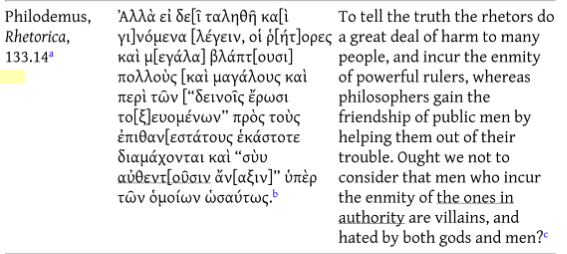

I came across a claim in a paper by Leland Wilshire [The TLG .. and αὐθεντέω in 1 Timothy 2.12, NTS Jan 88, p134] that the last clause means ‘sharing the house with murdered children’, and was wondering if αὐθένταισι could really mean ‘murdered’. The passive sense looks impossible to me, but I might be wrong..

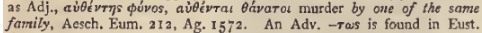

Elsewhere, αὐθέντης is used adjectivally on a couple of occasions in connection with φόνος or θάνατος to mean something like ‘of same kin’. Although there is a connection with murder the force of it seems to be more on the kinship side, to define what sort of murder it is. Admittedly, in connection with θάνατος, maybe it also conveys that it was a murderous death, as well as that it was kin on kin, I am not sure - the two cases are both in Liddell and Scott.

It is beyond my ability to translate the above sentence, but here is my best shot:

‘It seems the gods are in agreement with you

when anyone wants, by an oath, to escape from death

or chain or the violent evil of war,

or to share homes with [..] children’

That doesn’t make great sense, but it occurs to me that αὐθένταισι might just mean something like ‘their own’ - somebody wants to run away from war and stay at home. Can it really mean ‘murdered’?

Thanks for your help with this,

Andrew