For them, noon (中午) extends from about 11:30 till about 14:00. It used to be longer, but chairman DXP shortened it at some point. It is a time for eating, resting and not interacting with others. Nobody practices piano or has domestic arguments at that time. It is socially unacceptable to call or call on others. Government offices generally shut, in offices people lay out camp beds and sleep, and students mean forward and sleep on their desks.

What you are describing is a Chinese siesta. This is more or less what μεσημβρία means: not a specific point in time (unlike modern clock-regulated societies) but a vaguely defined midday period during which everyone abstains from strenuous activity, and its origins lie in agricultural work, where the heat of the midday sun makes activity not just difficult but dangerous. "Mad dogs and Englishmen . . . "

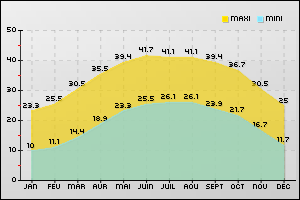

And, yes, the heat varies seasonally, but in Egypt, it’s hot all year round, and in any event, agricultural activity is generally concentrated in the hot seasons of the year.

In any case, Nonnus isn’t specifically referring to the weather inupper Egypt. The Dionysiaca is a poem, squarely in the ancient Greek poetic tradition, and he is invoking meteorological conditions prevailing throughout the Mediterranean world and elsewhere (even in China, apparently)at midday, when the sun’s heat dissuades activity and induces torpor. While I haven’t searched for this, you will find many instances in ancient Greek and Latin literature (and elsewhere) where agricultural laborers rest during the hottest hours of the day,

I

have found δειλη used by Herodotus for afternoon

But unlike modern “afternoon”, it’s not a time of day defined specifically to noon, a precise horological or astronomical instant. When Herodotus wants to be more meteorologically precise, he resorts to the phrase ἀποκλινομένης δὲ τῆς μεσαμβρίης, but that’s not a translation of “afternoon”.